When the darkest point is under the spotlight By Horacio Zabala

By Horacio Zabala

From a symbolic point of view, a journey is no longer the mere transit from one place to another. To travel is to search and discover, to experience and change. The heroes are always solitary travellers who combat ruthless monsters; they get lost, are shipwrecked and suffer the hostility of the gods. Finally, they are those who manage to pass from darkness into light.

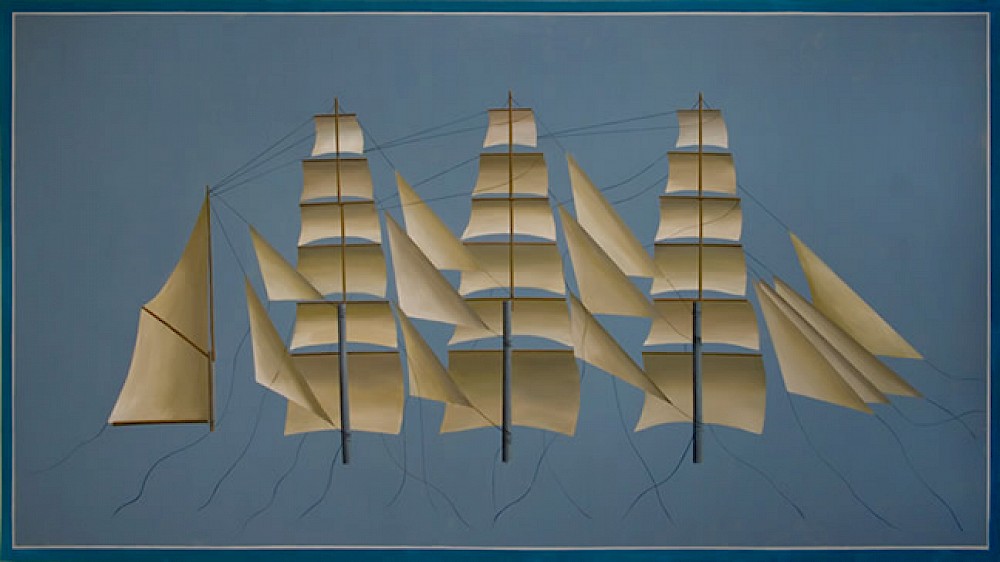

It is dusk. The wind blows and heightens the sails; we are well positioned. We have a fervent desire to arrive at our destination. We have strength, courage, resistance and tenacity, and we have a promise to keep and a last wish to utter. The wind blows and heightens the sails, but there is no boat.

This brutal absence (this lack of sense) amongst other absences that we are unaware of, motivated your decision to gain immediate entry to the star-filled sky. Your (unpardonable) action must be seen as free choice, planned and considered. We say that only a magnifying glass (an obstinate viewfinder) offers us the possibility to consider your very personal vision of existence and your jump into the void.

Animals don’t invent. Both the telescope and the lullaby are human inventions. History tells us that, before painting the Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was a military engineer in the service of César Borgia. In these circumstances, he thought (drew, dreamed, studied, invents) a sort of outlandish apparatus capable of flying by wind-power. We don’t know if he ever managed to build it, nor what his intuitions in respect to it were. Today, this proto-project demands to be seen as a celebrated antecedent of the development and acceleration of techno-science and the correspondent aesthetic of catastrophe.

In our civilisation of the integrated spectacle and permanent image, the same catastrophic (and at the same time trivial) aesthetic establishes itself not only in multiple objects, discourses and systems but also in the egoistic and hedonistic gaze of the subject that perceives them, such as in the homogenous, neurotic and repetitive postures of domestic life. “…I told you so, that you’ll never get a job, not to come home late, that I’m sick of your complaints, that you get worse every day, that I can’t stand you any more. I told you that you’ll never get a job, to eat slower, not to come home late, that you’re badly dressed. I told you that I can’t stand you any more, that you’ll never get a job, not to come home late, that you’ve got no manners, that you get worse every day, that I can’t stand you any more”.

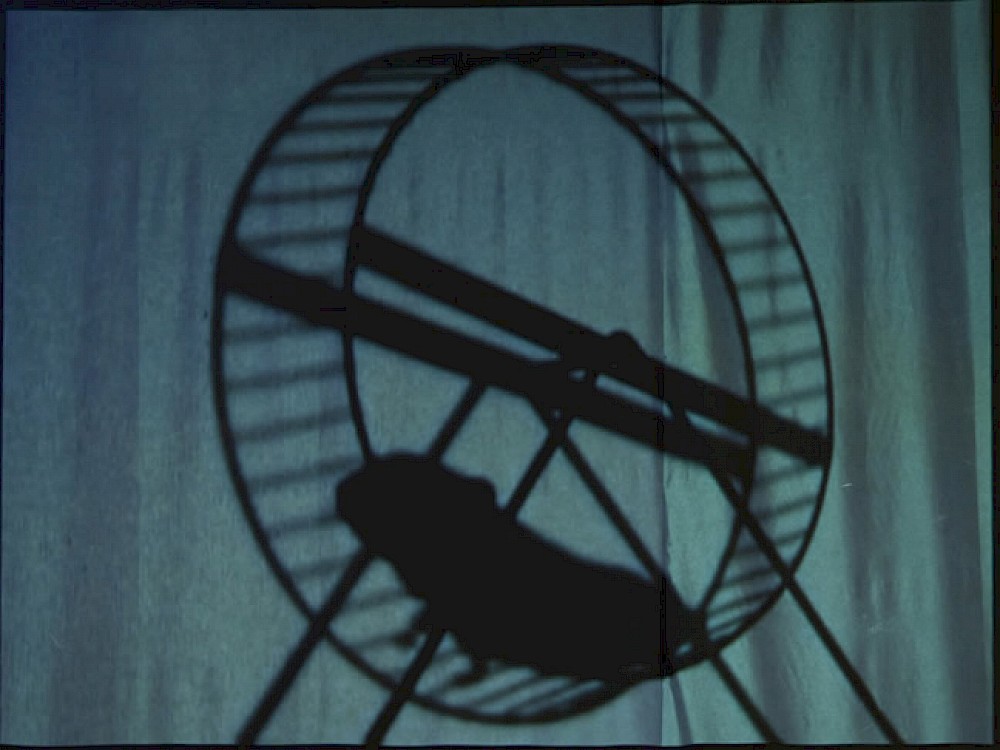

A video registers the repetitive movements of a rodent that is, apparently, addicted to the spinning wheel that is his eternal prison: a Wall of China made to measure. An installation is conceived with two objects: a rifle with a built in viewfinder and a cuckoo clock with its corresponding bird that, at exact and insupportable intervals, appears and says ‘cuckoo’. In other words, it is converted into a sitting duck for any would-be criminal.

My dear, even if you persevere and repeat time and again the same dance steps, you will never attain lightness, dignity or grace. Poor angel, for as much as you turn and turn once and again, your steps will never overcome the ungainliness of your body. Although you listen to the song of requited love and you return to dance once and again, you will never feel nor understand my love. To use a Hindu expression, you are lost forever in the wheel of reincarnation. No-one will send you letters now, you will only receive my poison arrows.

The globe is located in a cul-de-sac; the artist considers this favourable for its appearance as an aesthetic experience: so that in a space without exit, a (indefinable) stimulant is awakened in my memory and imagination, in my sensibility and knowledge, in my visual culture and conception of things in the world. It is evident that Fernando Lancellotti has wanted to ‘assign meaning’ to the world not only through form, colour, movement and positioning, but also through the words that constitute its title: Perhaps you’re not going anywhere.

In summary, on this occasion it imposes at the very least a question: who is it that perhaps is going nowhere? Well then, the vertices of the ancient triangle indicate the possible answers: 1) the artist, 2) the artwork, 3) the viewer.