|

Lancellotti’s collection held in Recoleta two years ago was called “Demasiado Fugaz” (Too Fleeting). Here stark silhouettes of people in familiar places and involved I everyday activities had imposed on their centre red digital numbers. The numbers were triggered by a sensor that increased by one as the viewer approached. “In this exhibition I was looking to recreate people in places that we could all easily recognize,” he said. “A type. Like business men sitting around a conference table”. Other figures included a woman pushing a shopping trolley and an old man lying in a hospital bed. In the middle of the conference table, in the middle of the shopping trolley and in the middle of the bed appeared a number. The gallery itself was dark thereby making the number more apparent.

Jorge Glusberg, Director of the National Fine Arts Museum, in his review of the exhibition, argued that the numbers that appeared in the work were to do with statistics. This was an interpretation the artist himself is in agreement with. “There are eighty million people born each year,” Glusberg wrote, “that is 219.000 every day. Three new inhabitants each second… Their names are soon lost in a sea of data… numbers that do not last, numbers that computers change each minute.” The black silhouettes represent us, the audience. An electronic device in them counts us converting us into a number; a number will change with the next spectator that follows us, converting them into a number, yet another number and without end.”

Lancellotti’s current exhibition is called “Cajas Negras.” (Black Boxes) “About a year and a half ago I heard the recording of a black box in the US,” he said. “A plane had crashed and killed everyone on board. It was in all the newspapers. You could hear people laughing and joking and just talking and suddenly nothing. The suddenness of that affected me a great deal.”

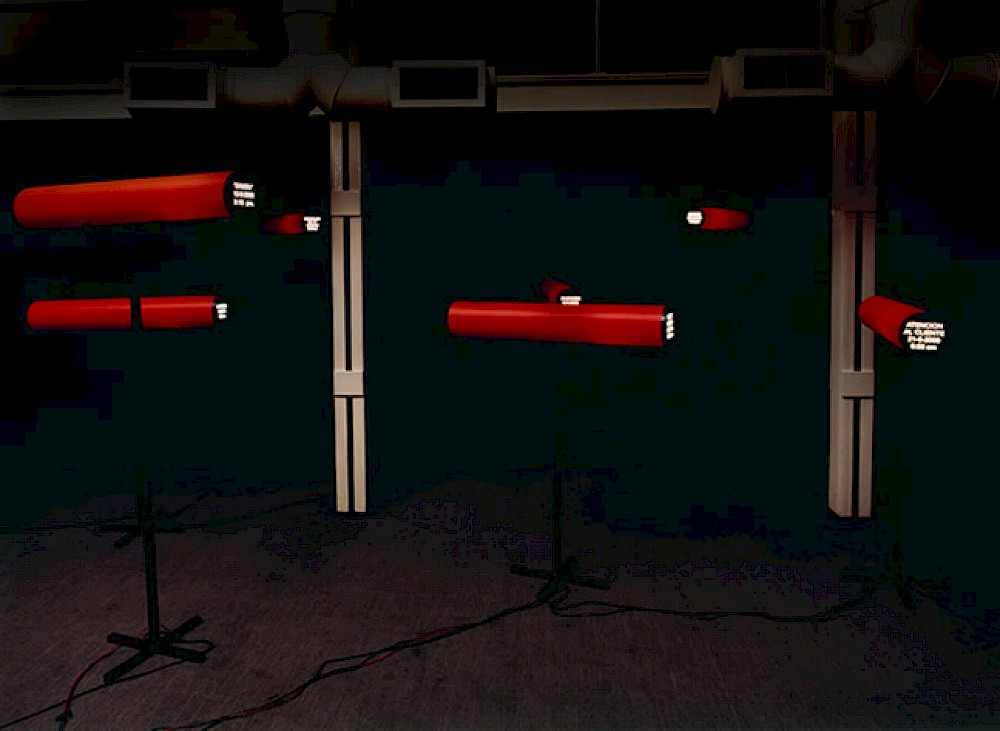

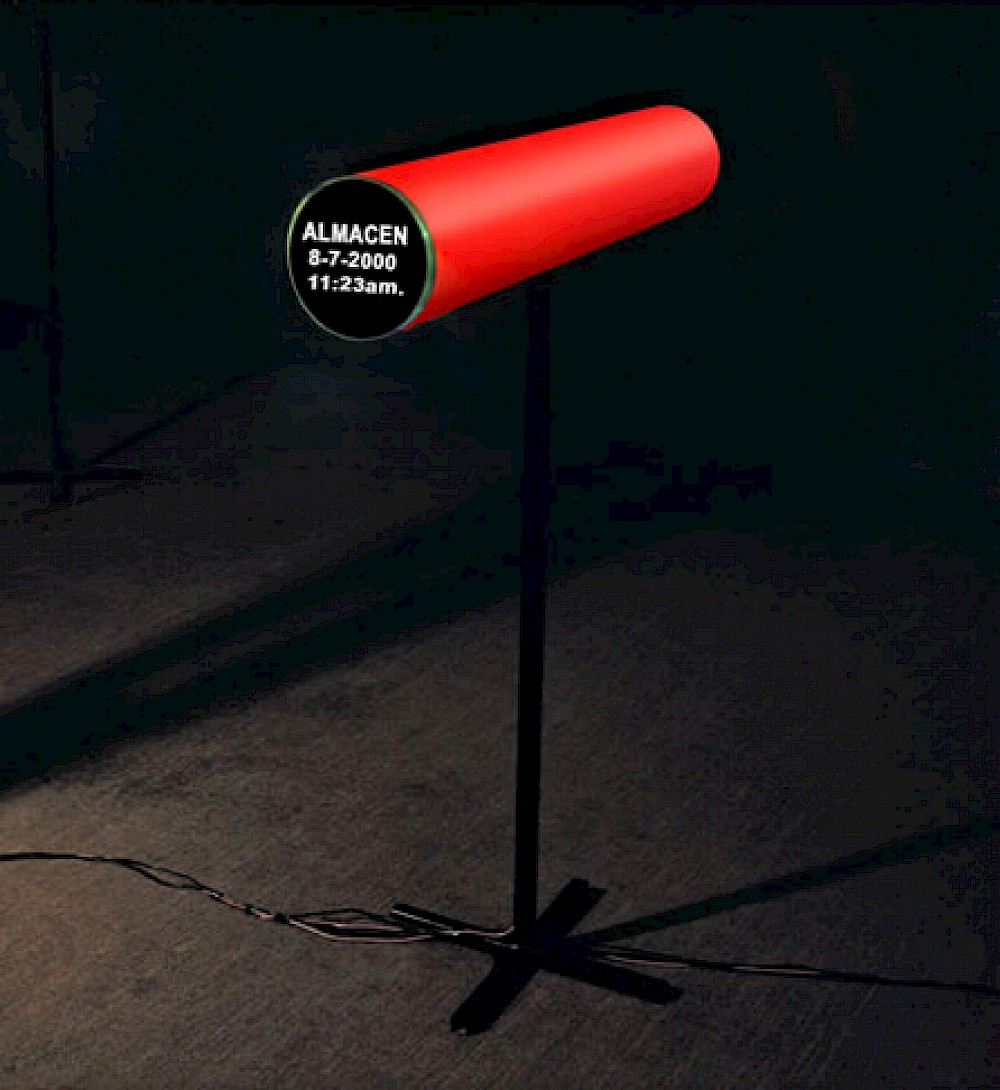

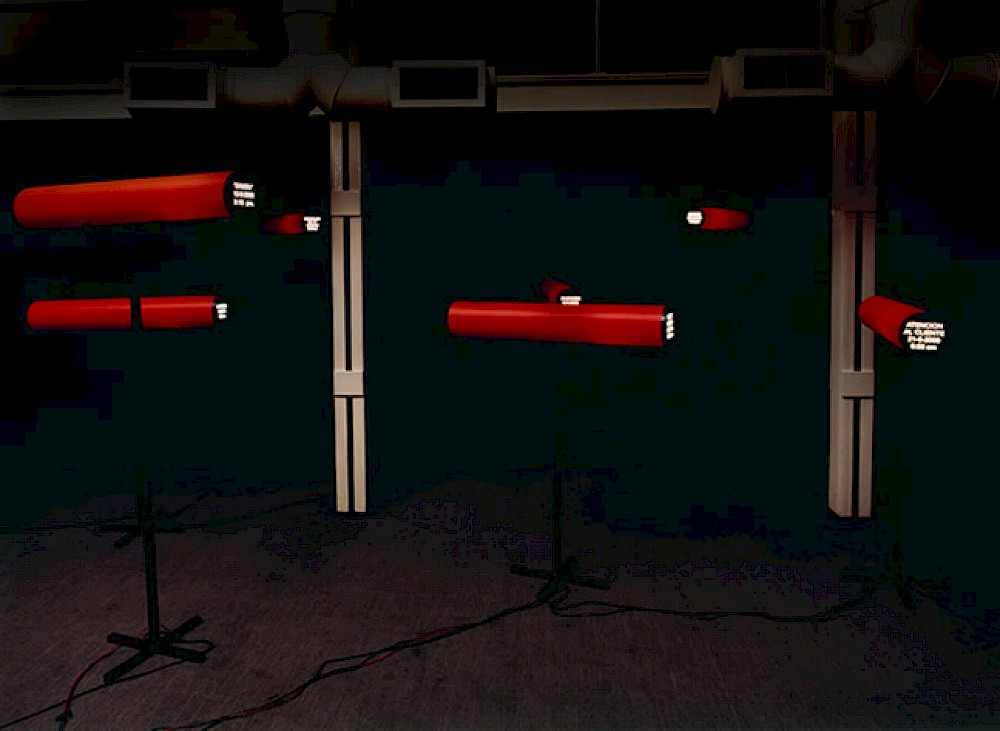

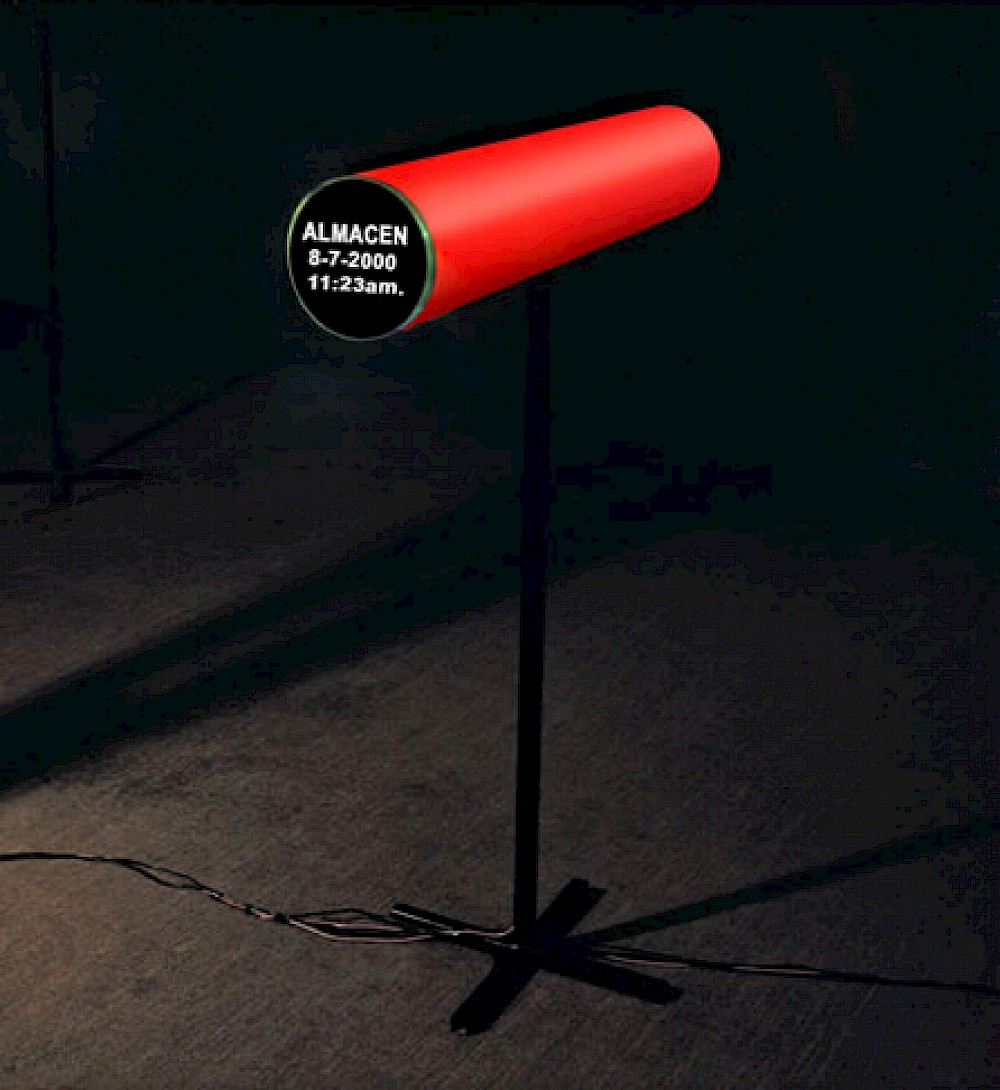

In this work eight tubes are mounted on pedestals. The tubes are the same phosphorescent red as the black box from airplanes. At the back of the tubes is a speaker out of which a recording is played. At the front of the tube are the date, place and time when that recording was made. This is illuminated in white. Each recording is distinct from the other.

One of the recordings was taken in the Subway on line D. Close up to it one can hear the sound of a man with AIDS begging for money rising above the murmurs of the commuters on the train. On another, “Honduras 700 – 800 2000 11:35” a street vendor continually repeats his sales pitch. From another speaker, children sing a nursery rhyme. On another, two women gossip. The sound is different depending on where one happens to be standing in the gallery and the sound changes as one walks around. Only when one is up close to a particular speaker does its sound emerge distinct from the others.

The recordings themselves were not made by Lancellotti. “I gave a tape recorder to around twenty people. They all had to record sounds for me and give me the tape recorder and the tape back within a week to ten days. They recorded whatever they wanted. Some recordings are more dramatic than others. I didn’t want to have any particular criteria or form. The phrases are picked out at random. The idea is to hear phrases or parts of a conversation that on their own are meaningless. When it was all over I had around forty-five hours of recordings in these black boxes to show that each person carries within them their own black box.”

In “Demasiado Fugaz” the silhouettes we see are anonymous but instantly recognizable. In “Cajas Negras” the people that we hear are strangers but the sounds they make are recognizable. These themes are given emphasis by recurrent dramatic style and will be continued in Lancellotti’s third work which is now on their way.

|