Fernando Lancellotti’s Playground of the Absurd -By Kate Stanworth

Argentimes 01-11-2008

Fernando Lancellotti’s Playground of the Absurd

By Kate Stanworth

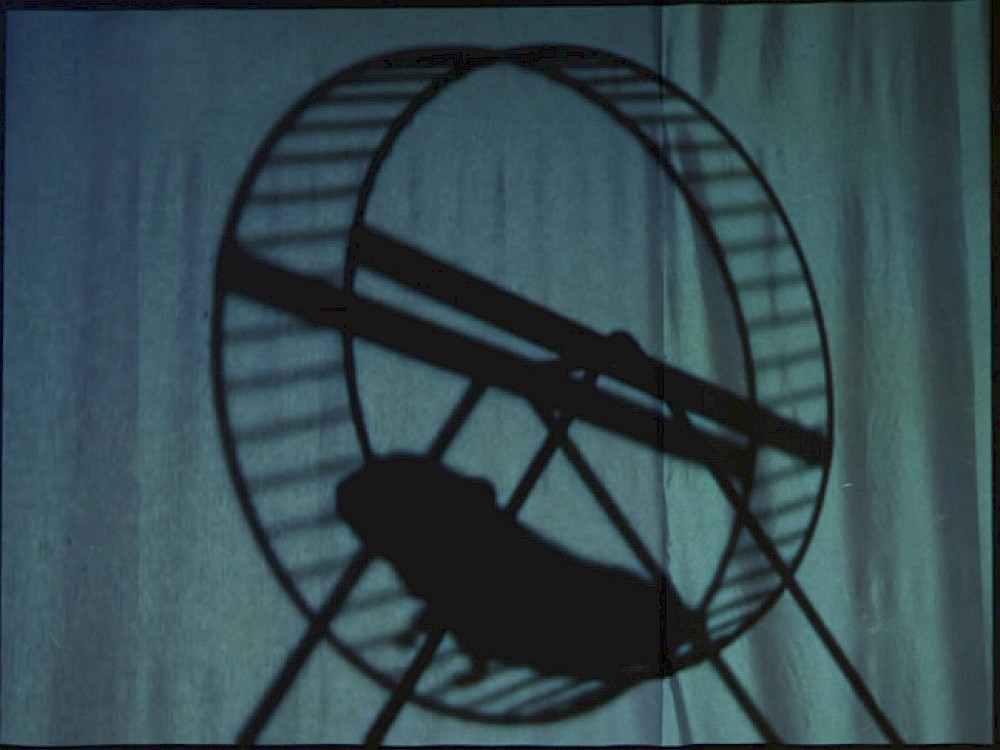

On the wall of Wussmann Gallery, Argentine artist Fernando Lancellotti projects the shadow of a mouse scurrying in a spinning wheel on an infinite loop. Watching the creature’s futile effort to get somewhere elicits feelings of sympathy. Is this because his fate is so easy to identify with?

Lancellotti’s mouse has a mythical parallel in the Greek character Sisyphus, who is condemned for all eternity to push a rock up a hill, which then simply rolls straight back to the bottom. Writer Albert Camus drew parallels between Sisyphus’s senseless drudgery and a modern life spent working in factories and offices.

The oblivious mouse appears quite happy to accept its banal task however, and since Camus added that such a condition only becomes tragic when there is a consciousness of it, our feelings of sympathy are perhaps misplaced. What’s more, there is no cage that keeps him there, so we can only conclude that the little rodent has merrily accepted eternal imprisonment of his own accord.

If we were to go further down the road of absurdist rodent-human metaphors (and exploring these farcical possibilities is the joy of Lancellotti’s darkly comic show), we might be reminded of Jean Paul Sartre’s proposition that humans, like the mouse, also choose to incarcerate themselves in pointless habit rather than face existential questions about the meaning of life. Immersing oneself in pointless routine might be tragic, but it beats staring into the scary unknown.

This piece, along with Lancellotti’s other paintings and installations, is laid out in the spacious open plan gallery, making a kind of absurd, existential playground for the imagination.

The rodent is not the only character that appears to be an automaton stuck in mechanical routines, with the comic absurdity of a Beckett play. From a record player in a domestic cabinet, a woman’s voice repeats the phrase ‘I told you so, I told you so’ (‘te lo dije, te lo dije’). The cabinet sits on a carpet complete with model boat on top, a bizarre living room taken out of context. Reduced to just another piece of domestic machinery, the woman becomes a powerless caricature.

Meanwhile, across the room, another creature is also doomed to a domesticated routine that leads directly to its demise. A cuckoo in a Swiss style clock has been sped up to announce the time every fifteen minutes. Its predictability is set to become its very undoing, since a shotgun on the other side of the gallery has its crosshairs firmly set on the bird.

The motif of mechanical animals seems to lead on from a previous work, ‘El Secreto’ (The Secret) in which the sound of birdsong comes from an invisible microphone inside a metal fencing mask. Is this antique mask a metaphorical cage, another manmade prison? Or is the egg-shaped dome protecting the bird from attack? This time, unlike the cuckoo, mouse and woman, the creature’s hidden, mysterious status seems to protect it from being reduced to a caricature. “It sings as though it were divulging the codes of another world,” says the artist, but since the cipher can’t be cracked or domesticated, it remains enigmatic.

It is not only animals that are anthropomorphised by Lancellotti, but also objects, such as two tires that sit intertwined with each other on a plinth. Their ‘romantic’ embrace, however, means that neither can go round and they remain in a position of pathetic interdependence.

‘No-one Sends You Letters Now’ is another collection of allegorical objects – this time more than 60 arrows suspended from the ceiling by invisible thread. “These are hunting arrows,” says Fernando, “but the patterns on them are similar to those of air mail envelopes. Arrows hold associations of cupid, of love. They’re both romantic and aggressive.”

Lancellotti detaches objects from their function in order to expand their poetic potential and create what he describes as a ‘kind of sarcastic amusement park’.

“There are metaphors,” he says. “I work with objects that are castrated. None of the objects that you see can arrive at their destination.”

“Take, for example, a balloon that goes up to the ceiling of the gallery and down again but can’t get out.” The balloon appears to be making a bid for freedom, and yet its longing to escape only brings about another pointless repetitive exercise. Just as the Theatre of the Absurd’s characters may find themselves impotently trapped in a routine or story, Lancellotti’s objects appear to be incarcerated in the gallery.

Like the balloon, other works refer to the longing for flight and freedom. ‘La Ultima Plegaria’ (The Last Wish), for example, is a three metre wide painting of a frigate’s sails that have been liberated from their connection to the boat. In a dreamlike vision they remain suspended in mid-air with their ropes flailing in the wind. In another work a trampoline mounted on the wall is painted with an image of the universe. Is this the ultimate destination of an ambitious jumper who wants to leap into the void?

‘Canción de Cuna’(Cradle Song), in a similar vein, is a painting of an umbrella that has been morphed into an unknown object. “You take away the handle and it’s not an umbrella anymore,” says Lancellotti. “It could be a paraglider or a hat or a dress. The intention is that it is a type of flying object.” The work displays echoes of Magritte’s painting of suited men taking off into the sky with their umbrellas, engaged in an escape from bourgeois ordinariness.

Despite the similarities that could be cited between his work and that of surrealists such as Magritte, Lancellotti is keen for his work not to be pigeonholed.

The label he is especially resistant to though, is that of ‘conceptual artist’. “I use objects and images with an existential charge, not conceptual.

He explains that the work is inspired by the combination of coincidences from everyday life. “My intention is to make the everyday strange. It’s the street where you find ideas, not the studio.” In turn, each viewer brings their own associations and memories to the everyday objects and sounds they encounter in his installations. “It is open, and every person has a different interpretation of the work,” he states.

Most of all, we cannot help but empathise with his cast of strange animals and inanimate characters. Perhaps we too are willingly trapped in a routine prison of our own making like the mouse, or longing, like the balloon, to launch into the unknown? Whether the exhibition brings you comedy diversion or existential angst, we can perhaps be reassured by another of Sartre’s proposals: that the first step to becoming truly human is to embrace the absurd.

|