From adversities we live - By María Gainza - Página 12. Sup. Radar 30-11-2003-

Far from that romanticism that finds additional charm in hostile settings for creation, lacking every ‘for export’ Latin-American cliché, and even further from adapting their work to foreign labels such as ‘arte povera’ or ‘conceptual art’, the collective exhibition by Lancellotti, Navarro, Amespil, and Kampelmacher inverts the idea of adversity, turning a situation in which one lives into another from which one makes a living, just as if artists could take advantage of it to make the necessary adjusts and set their minds into what matters.

By María Gainza.

Sometimes plan B works better in the end. When everything’s lost, we rack our brains, our nerves jangle, we frown slightly, and out comes an idea —that intermittent little sparkle in the back of our heads that says ‘come on, grab me fast’, because we’ve just found that spot where –at last, but only for a moment– our thoughts fits like two pieces in a puzzle that click into place.

Something in the like must have happened to Karina Guerrieri —curator for the Fundación Centro de Estudios Brasileños (Centre for Brazilian Studies Foundation)— a little more than two weeks ago, when the End of Year Exhibition was suddenly cancelled. She stared at the middle of the hall empty-handed, with nothing to hang but herself. It is not known whether some kind of ghostly Hamlet’s father-like appearance got before her, but it’s for sure that this curator-in-catastrophic-situation’s mind was suddenly crossed by the father figure of Hélio Oiticica, and his words: ‘da adversidade vivemos’ (from adversities we live). So the name remained. And there also remained the intuition to make an exhibition that states how artists working in situations that are far from being ideal and with only what is close at hand manage to shape their very private obsessions. What unites Amespil, Navarro, Kampelmacher and Lancellotti is not mainly the similar socioeconomic context, but a conceptual echo, which throws arrows in many directions instead of stressing, and the attitude of entering 21st century as insistent as a little tractor that drags through its path all that the others discard.

The funny thing about the expression ‘da adversidade vivemos’ —taken from a text written in 1967 by Oiticica for the New Brazilian Objectivity exhibition at the Rio de Janeiro Modern Art Museum, where the artist stressed that a great part of the works’ character and strength arose from the extreme fragility of life in Latin America— is that it was also the name of an exhibition cured by Argentine critic Carlos Basualdo at the Modern Art Museum in Paris, in 2001. But by that time, Basualdo was already playing at the big leagues, and his dream team included Cildo Meireles, Victor Grippo, Meyer Vaisman and Minerva Cuevas, among others. The thing is that Granieri didn’t know about Basualdo’s exhibition, but anyway he was cautious enough to use the expression for a hybrid situation between the quote and the title, so there would be no misunderstandings: first of all, his is an exhibition that’s far from the bucolic romanticist idea that creating within hostile conditions provides an additional charm. There’s neither ‘for export’ Latin America nor ‘rubbish aesthetics’. And it’s even further from trying to reduce the works to a peripheral discourse or to adapt them to foreign labels —these works cannot be categorized neither as ‘arte povera’ nor ‘conceptual’ or ‘postminimalist art’—, and that’s something to be grateful for. But while the artworks gathered by Basualdo in that opportunity spoke about corruption, military power, misery and the fierceness of inequities, here the accusing finger stops pointing so vehemently. It’s true that Latin American adversity —trying hard to make us fall every day— is the context in which a lot of those works were made, but far from any pamphlet, here the idea of adversity is not related to a situation where one lives, but to one from which one makes a living, as if artists took advantage of it to make the necessary adjusts and set their minds on what matters.

Take any item from the shelves of Ignacio Amespil’s laboratory and witness the polisensorial quality of his objects. Every sense —of touch, smell, sight, taste— is summoned. Over nine white shelves that were once spotless, but are now covered by thin layers of dust, the artist gathers moth-eaten objects: test tubes, fat, yeast, sulfate, medicine, pills, experiments, jelly parasites, flask, ampoules, sodium, pipettes —it feels like those rooms where disorder is systematically organized. Don’t think of Mauricio Doval’s laboratory artefacts, but instead of an abandoned shelf in some public hospital. These objects once had a useful life, and are now exposed here like junk filling with rust and smells. It’s so unusual to find these instruments, usually associated with an almost chirurgical state of cleanliness —those instruments which shine in all their polished splendour in Cronenberg’s ‘Dead Ringers’ —, now dirty, rusted and sticky, that it feels disturbing to look at them. These objects stray from the idea of ready-made and take part in the artist’s everyday life, they’re ‘subject-objects’ instead of ‘object-objects’, as Duchamp wished, and that attitude reminds us of Joseph Beuys’ cabinets. And then, science and technology called into question: new shapes of matter projected on dripping foam, battered parasites, and experiments with gelatine that spills in the shape of a virus.

When Linneo created his Sistema Naturae in 1735, he believed he had found a method for building an ideal taxonomy of natural shapes, which thus tended to adopt the shape of logic —each species in their small box. Every formation unable to fit within these labels was a freak to be categorized as monstrous —Darwin had found the incubation focus of mutations in the colonies—. With his unusual parasites and tentacular crystallizations, Amespil weakens the myth of positive knowledge of shape. So there is a coming and going all the time, flirting with science and at the same time boycotting her right when she was starting to get very full of herself.

There’s someone Amespil’s mutant and displaced artefacts does get along with, and that’s Eduardo Navarro and his drawings. His delightfully funny works revolve around crazy fantasies —vans filled with chickens with parts that don’t fit (just like those BMW owners who couldn’t get spare parts once the exports to the country were over), a gigantic electric fan balancing over something that could be a soccer goal or rather a stiff little Playmobil-like man who holds on to a teddy bear solar lamp to sleep. When the U.S.A. developed the gadget industry —small ingenious devices, like ballpoint pens that take photographs, or keys that record conversations—, surely the aim was to offer an Agent 86-like world for the detective fantasies of common people. But the gadget that reaches Argentina in Navarro’s images seems a bit precarious, especially carrying an almost involuntary humor. Navarro does not seek; his ideas rather escape from him.

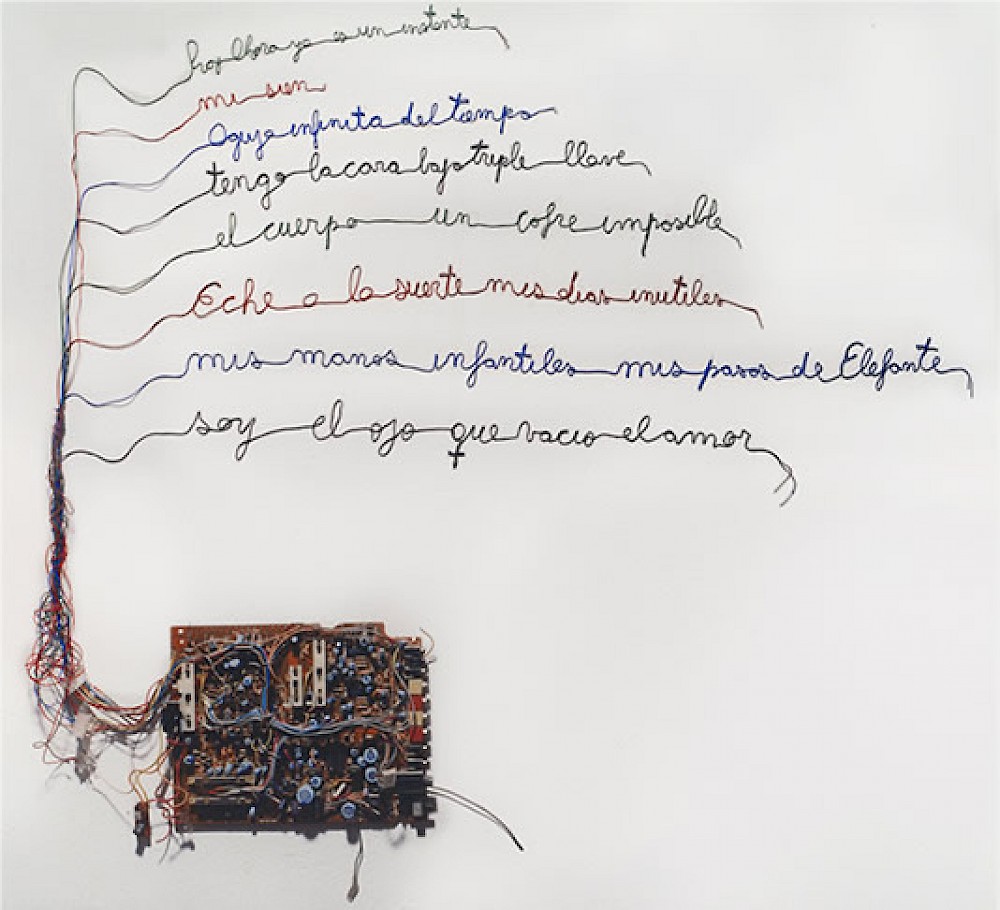

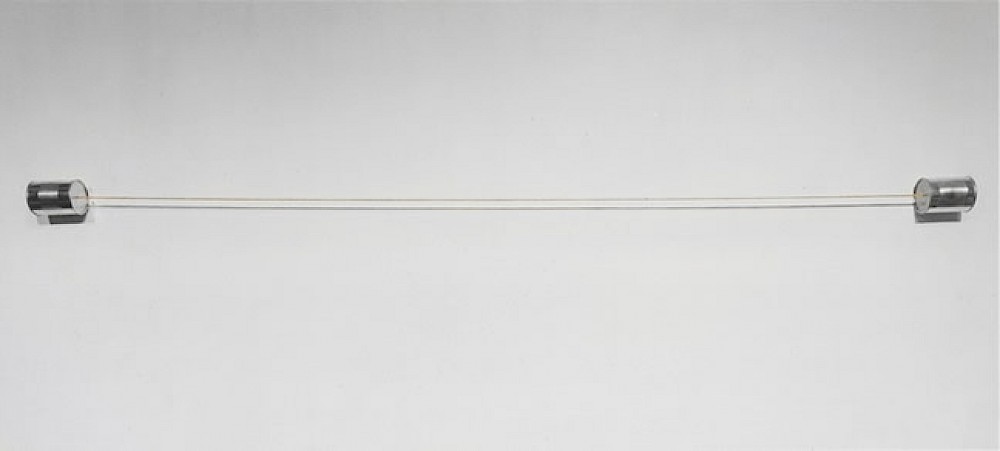

Cynthia Kampelmacher works with minimum gestures: silent boxes piled one over another showing the tracks of a match, like small stripes on a minuscule blackboard. Beside there is a graph paper sheet where somebody killed time redrawing the little squares with fibre-tip pens. Both works point out those intimate, automatic movements incorporated by us as a muscular memory. Then come the green spaces, cuttings from a map hanging frailly on the wall, ready to be blown away with the first breeze, and small polythene bags that keep inside bits of streets and dust swept by some broom —a tremendous synthesis of how knowledge is always fractured information that may circulate, that can be taken here and there, but is constantly looking as though it was about to collapse, and never reintegrates as a whole. This leads us to entropy, the tendency of matter to move from states of organization to disorganization, which appears in its most poetical form through Fernando Lancellotti’s work. Information regarded as a series of data in constant danger of crumbling seems to be at least one of his worries: two cans and a tightened string registering unstable telephone conversations, a tangle of cables straightening for a farewell message, and all the time that feeling of a precarious order, of chaos held with pins.

They say that in the Brazilian city of Campo Magro a collection of articles found by street cleaners is kept at the Trash Museum. The works in this exhibition share that defying attitude of working with what’s at hand, without putting too much emphasis on the perfect making or the ultra mega technology. So, adversity doesn’t gather works linked together by a physical map, but instead by an intuition that boosts the idea of art not as static and canonized objects, but rather as cultural artefacts that flow within a territory where nothing is sacred or hermetically sealed. This garage sale attitude is condensed in those works based upon materials invisible to us because of their daily existence —Kampelmacher’s little white sewing box as a paradigmatic example—, where the urgent need remains of seeing what happens when, instead of rejecting them, you push them a bit more towards the spotlight.

https://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/radar/9-1089-2003-11-30.html